Rebel on the rez: Charles loloma

by Victoria Thomas

“The purpose of myth, therefore, is to both reveal and conceal. To tell what we have seen and disguise it, to mask God’s forked tongue.” – Rikki Ducornet

The iconic jewelry of Hopi jeweler Charles Loloma presents us with objects that speak, expressing a singular worldview with a technical mastery approached by Scythian goldsmiths, stone-setters of late-Dynasty Egypt, and the enamelists of medieval France, but otherwise unmatched in history’s bijoux.

Charles Loloma, whose name means “beauty” in the Hopi language, endures as an amused contrarian. To touch a piece of his coveted jewelry, now recognized as national treasures by UNESCO with many signed originals housed in the Smithsonian, is to begin to understand. Indigenous stereotype falls away at the feel of glossy slabs of turquoise, onyx, sugilite, lapiz, spiny oyster, coral, agate, opal, set vertically on end in an upright position, like books on a shelf, rather than flat-laid and inset. The setting defies gravity as well as expectation. For tactile contrast, Loloma sometimes combined tufa casting (“sand casting,” often done in a cuttlebone, the soft, chalky, white calcium wedge taken from the body of a cuttlefish, often seen in pet bird-habitats as a beak-sharpener) with inlay, creating a binary dialogue of rough against slick.

In a 1985 interview with Sunset magazine, Loloma was asked about how he navigated not two, but three worlds: the Hopi world challenged by modernity, the majority white world, and a third, more rarified mesa, the world of celebrity. Cher, who for a time claimed Indigenous (Cherokee) ancestry then wisely recanted, had recently become one of his most celebrated collectors. Even in 1985, a Loloma cuff might sell for more than many working Americans earned in a year. A Loloma necklace purchased by Cher was famously compared in price to a tract home in suburban Flagstaff. The tract-home cost a little bit more. The actress-singer, who is Armenian and Anglo, later donated the necklace to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Unlike his contemporaries who used turquoise as the main event, Loloma tended to use turquoise sparingly, sometimes setting the stones in 18 karat gold in place of the usual sterling, and accenting with the occasional diamond-- unheard of in the jewelry of the American Southwest at the time. Although he was known to cancel gallery openings or decline invitations to travel in order to attend traditional ceremonies on the mesa, Loloma was an iconoclast who refused to be limited by the confines of white society, or his own.

His work is eloquent and anything but silent. The saturated desert colors of his home on the Hopi Pueblo Third Mesa in northern Arizona, sliced into a seemingly improvised (although carefully chosen) jumble (procession) of rectangles, dance around the wrist or finger with a jazzy joy familiar to some from Gee’s Bend quilts, a jaunty, irreverent riff that takes flight from dry roots of privation, loss, grief, and anger. The upright construction seems to reference stories still sung by the old ones, from the time before time when Hopitutskwa, the Hopi homeland, was entirely flat. Sparkling, luminous breath-beings, perhaps katsina (this is the preferred spelling of the name for the ancestors and helpful supernatural beings according to the Hopi Tribal Council, although many continue to use the more common spelling, kachina), walked over the vast land table singing. In response to their song, the surface of the earth began to undulate and ripple, and rose up to form the peaks of sacred mountains. To a geologist, this reads like a poetic description of the violent tectonic shifts that formed the topography of the American West during the late Paleozoic some 280 million to 320 million years ago. In this way, a Loloma cuff is a dance, a song, perhaps a way of praying.

At last, he said, “You know, I feel a strong kinship with stones, not just the colorful ones I use in my jewelry, but just rocks I pick up at random when I’m walking around. I feel the stone and think, not to conquer it, but to help it express itself.”

In response to Sunset’s question, the artist slowly reached into his pocket, fumbled for a few moments, and drew out a white pebble. He set the pebble down on the edge of the desk and stared at it intently. The interviewer described a few minutes of silence, awkward for her, but apparently not for Loloma.

While the movie Indian of Hollywood westerns is stoic, humorless, as stiff as his cigar-store replica, Loloma’s spirit as released in his work is anything but wooden, yet he often told reporters that “Native Americans give the shortest interviews in the world” (and he’s right). He was predictably low-key when asked to explain his radical decision to set stones perpendicular to the metal housing. He cited the cliffs and bluffs as his inspiration. Did he sing-pray while working? There is no answer. Although a prominent member of the Badger Clan and a snake priest, the artist never talked about religion.

The idea of humor contradicts the white expectation of being Indigenous, an error nourished by white guilt. But here’s an inside joke: in the realm of Native-made jewelry, a shopping spree in Santa Fe will yield hundreds of pieces signed “Begay.” This commonly used surname may be the local equivalent of “John Doe.” Hopi and other Indigenous people will gently deny this, or more often simply ignore the question. For those Anglo-and-other tourists and visitors lucky enough to witness annual dances on the ancestral grounds -- versus in the lobby of a deluxe hotel -- asking questions of the dancers may elicit a slow smile. Taking photographs definitely will not.

Interviews with later Hopi jewelry artists reference wholeness, and the way that jewelry-making is not an act which can exist in separation from the whole of Hopi society. While Western art tortures itself with academic definitions, especially the delineations between “art,” “decorative art,” and “craft,” these doctrinaire distinctions seem absent from the Hopi creative process, at least as discerned from readily available conversation. To generalize, Hopi answers are rarely if ever definitive in black-and-white terms. Likewise, the Hopi expression of time is that the past and present exist simultaneously, a cosmic idea which has appealed to the past few generations of far-out, buckskin-fringed college students and SCOBY ranchers.

Refusing to identify a hierarchy within creative acts may also seem like another veil, yet another scrim by which Hopi shield themselves from probing scrutiny by a historically hostile and exploitative majority. A common statement made among Indigenous artists and dealers in the Southwest in general is that all creative acts honor the Great Creator, so cooking beans for your family, writing a master’s thesis, weaving a blanket, teaching children a dance, carving a museum-bound bulto and repairing a trusty saddle all carry equal cultural value. With this as background, Loloma and Hopi artists often work in several mediums of expression simultaneously; Loloma himself began as an illustrator and muralist.

He later ruffled feathers, including eagle feathers, by protesting the distinction made by white lapidaries and jewelers between “precious” and “semi-precious” gemstones. Traditionally, precious stones are identified as diamond, emerald, ruby and sapphire. Amethyst was once included, until huge veins of the purple gem were discovered in Africa, severely lowering its value. The Big Four as they are still known are generally valued most in dazzling faceted form, although astonishing cabochon specimens exist. The faceting of these super-hard, high-refraction gems, diamond being the hardest at a 10 on the Mohs scale, is a journey-story unto itself, an art and craft which was a jealously guarded Hasidic secret until this very day. Loloma freely utilized these priciest of gems, setting them side-by-side with pieces of polished wood and river rock. Anglo dealers and fellow Hopi often expressed confusion and disbelief at these choices.

Today, contemporary Hopi artist and writer Ramson Lomatewama is known in book-loving circles for his several volumes of poetry including “Drifting Through Ancestor Dreams.” Lomatewama states that he is unable to write poetry without also carving “old style” katsina, making silver jewelry, and blowing glass, the latter a skill he acquired while teaching Hopi culture at the Rockwell Museum in Corning, New York. Lomatewama creates glass objects as a way of honoring the legacy of Hopi pottery, but is prohibited from working in ceramics since clay belongs exclusively to women and girls according to Hopi ways.

Much to the alarm of his community, Loloma even rejected this restriction, not only by making pottery, but by throwing his pots on the wheel versus hand-building with the far more ancient coil method. In fact, it was ceramics, not jewelry-making, that initially put Loloma on the map as an artist. After completing military service, the G.I. Bill made it possible for him to begin studies in ceramics at the School for American Craftsmen at Alfred University in Alfred, New York. There, he received a fellowship from the Whitney Foundation for research in ceramics on the Hopi rez. In 1954, he and his wife opened a pottery shop, and called their pots Lolomaware.

He gradually and organically found his way to metal, fire, and stone. A smashing success in Paris launched what would become the most visible and lucrative aspect of his career. Jewelry carries weight in Hopi life, as it does everywhere. In the case of Hopi-made jewelry, the value is measured in story, beyond the obscene price of precious metals and the increasing scarcity of local gemstones. Pieces of jewelry may contain coded messages, like the jacla pendant or earring symbolizing corn, abundance, life, endurance. The use of a specific color or the repetition of a pattern used in textiles and pottery suggests a singing, song-line, story, drumbeat, prayer. For any culture which has withstood genocide, the pattern of story is more than simply a way of remembering: it is an act of resistance.

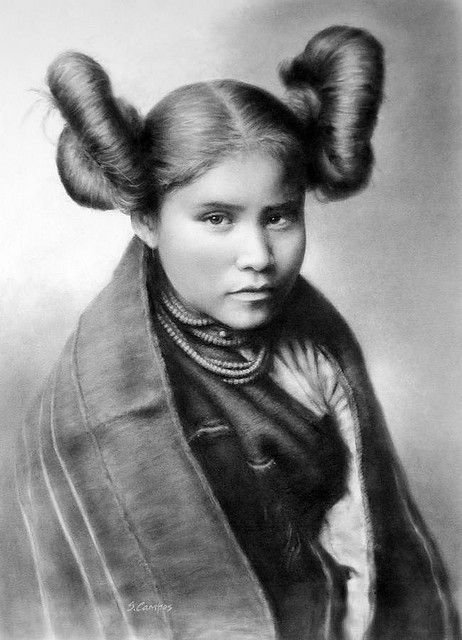

Loloma made many Indigenous people uncomfortable simply because he wasn’t content to reproduce high-end versions of designs which were familiar to Anglo tourists. Beloved depictions of hunchbacked flutist Kokopeli, howling coyotes (bandana optional), and the squash-blossom necklace are the most broadly distributed examples. Instead, he took inspiration from world cultures beyond his own, with particular interest in Etruscan mosaics and Egyptian art. In his earlier ceramic work of the 1950s, Loloma created Egyptian-style friezes with characters wearing the iconic “squash blossom” or “butterfly” hairstyle of young Hopi women worn to signal their availability for courtship.

Later at his jeweler’s bench, he made daring use of imported pearls, opals, moonstones, and gold, inviting scorn from Anglo dealers as well as fellow Hopi and other Indigenous artists who said his work wasn’t “Indian enough.” This opinion was shaped by the expectation that collectors and tourists wanted more of that to which they had become accustomed.

The thorny notion of authenticity continues to be relevant, in light of the fact that many people, from former Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren to “Sacheen Littlefeather” (real name: Marie Louise Cruz), love to lay false claim to Indigenous ancestry. Wishful thinking, and ironic. Less than a century ago, such ancestry was often disguised and denied for safety and easier assimilation. As recently as the early 20th century, Hopi and other Indigenous children were put into Bible schools and federally funded boarding schools where they were punished for speaking any language other than English. This alone may account for generations of First Nations people who tend not to be chatty.

And yet, as commoditized and commercialized as the “Southwest” has become as a fashion and home décor meme -- from Robert Redford’s Sundance catalog filled with imported silver-and-turquoise jewelry to Ralph Lauren’s deluxe cosplay of cowboys and Indians -- the allure persists, even in the face of faux authenticity. And the essence of genuine Indigenous work remains elusive.

Loloma considered what he called the use of “inner gems” as his greatest innovation, sometimes setting the most valuable stones used in a ring or cuff on the inside surface, placing the gem surface into contact with the wearer’s skin, invisible to the outside observer.

Occasionally, he would cast or saw a small opening in the outer surface, revealing the hidden treasure beneath. This sense of inner-outer duality is especially relevant in any encounter with Indigenous First Nations art. It’s also evocative of a more global mysticism. For example, the Zohar or Book of Splendor cautions the observant that the face of G-d is often hidden from sight, but that it is always present even when unseen.

Just as Loloma’s dramatically stacked “height” bracelets and rings suggest the jutting cliffs and canyon walls of his landscape, his juxtapositioning of grainy tufa surfaces with sleek, polished turquoise resonates as the cycle of dry arroyo and fast-moving water, drought and flood so familiar to any desert-dweller. And his work, including his controversial use of materials not included in the traditional Indigenous narrative, is revolutionary in another way: Loloma’s jewelry elevated the work of Indigenous artists beyond the realm of the trading post and souvenir gift shop. This re-contexting was a long time coming, and remains incomplete, in that Loloma’s work still may be viewed reductively as “ethnic.”

Loloma made art with a level of daring absent from traditional forms, boldly crossing boundaries and even burning bridges. In a culture desperately trying to reclaim itself, Loloma refused to obey those aspects of Hopi dogma that didn’t suit him. Faced with centuries of Eurocentrism, he fearlessly stepped outside the ways in which Indians -- by any name -- were expected to create. In Loloma’s sphere, diamonds, pearls, and high-karat gold take their place alongside saddle-worn denim, frybread, and the harsh perfume of woodsmoke and chilis roasting in the autumn air. In this sense, he belongs neither to the restricted world of his forebears and their conservative descendants, nor to the alien and uncomprehending world of non-Indigenous people. Instead, long after his death, Loloma continues to occupy a unique realm of his own devising, created moment-to-moment solely through the power of his own ideas.

All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.