The third thing

by Victoria Thomas

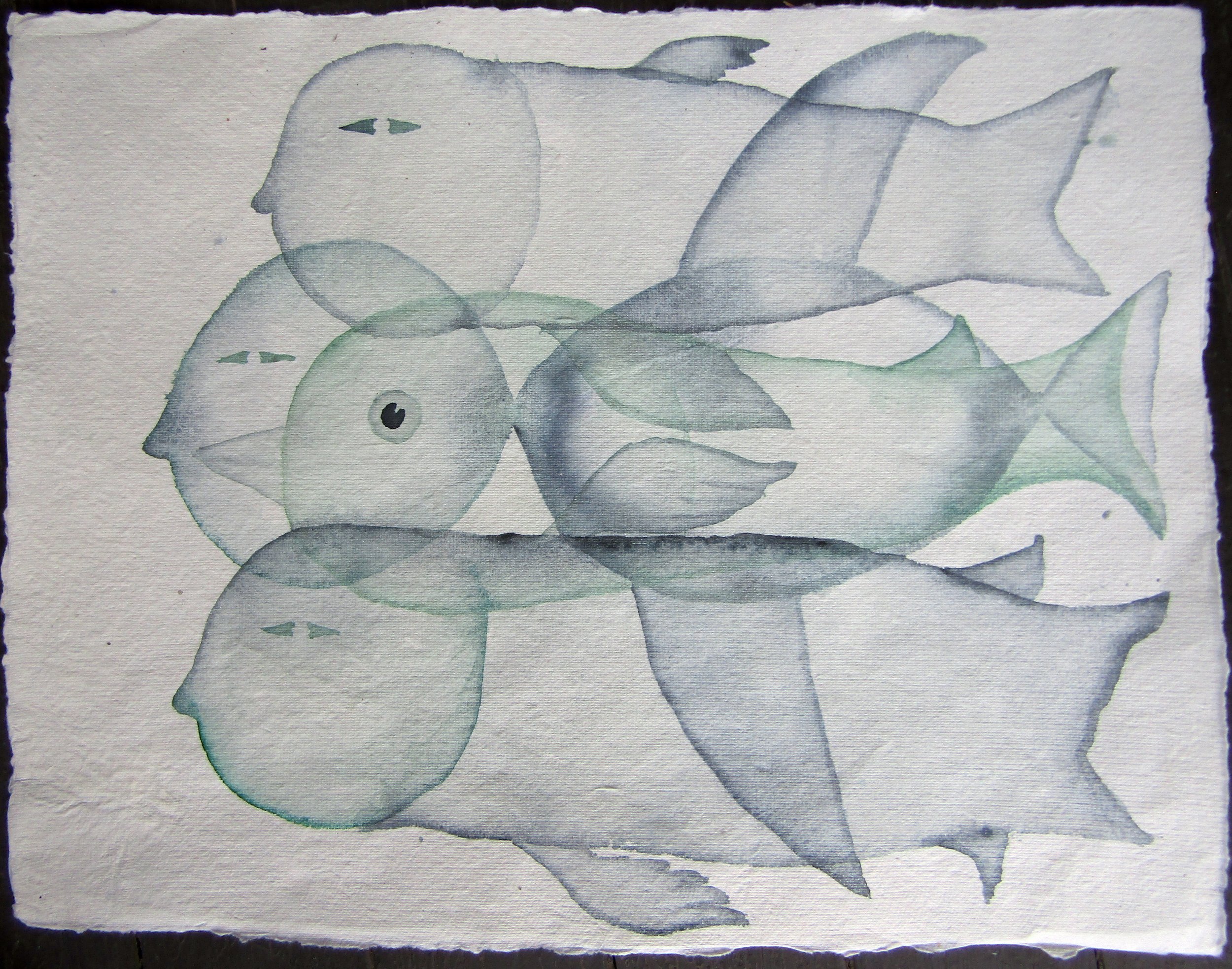

The paintings of multi-gifted Donald Saaf stir subtle, surprising sensations on the skin and vibrations in the memory, hauntingly familiar yet entirely strange. Saaf says he works in triads, referencing what D.H. Lawrence called “the third thing”:

Water is H2O, hydrogen two parts, oxygen one,

but there is also a third thing, that makes it water

and nobody knows what it is.

The atom locks up two energies

but it is a third thing present which makes it an atom.

“The Third Thing” — D.H. Lawrence

The ancients might have called this the “quintessence,” the fifth, not third, thing, the ether which transcends earth, water, fire and air. Saaf, however, works in threes. “I tend to triangulate into triads, the composition, the colors, the idea underneath it all,” says the artist. “A trio of colors is like a chord, and doing this keeps the eye moving.”

At first blush, his compositions seem to sway in deep water, as if submerged in half-sleep, or arising from the seahorse-shaped hippocampus. Swedish folklore and Greek myths surface throughout the work, but the artist doesn’t love the usual descriptions like “whimsical” and “naïve” which are casually applied to his dreamy figural pieces.

Saaf has illustrated children’s books, taught at the progressive Putney School in his native New England, and created “crankies” or puppet and marionette tabletop theatres which feature a scrolling backdrop turned by a crank. But the initial transparency and seeming innocence of his characters on paper and canvas, who often inhabit elongated, chimera-like hybrid bodies combining human, aquatic and avian anatomies and are crowned with halos, is short-lived. A longer look at the work imparts the sense of a deep and mysterious current forming the images. He says, “These ‘ghost’ images become a literal manifestation of the larger spirits of the figures; the life energy that is too big to be only contained inside the body”. He talks of “…ghosts of memories, of symbols that show us the inside and the outside at the same time. Again, walking in a city, you might feel tiny, or like you’re floating above everything. The spirit is connected, but much larger than the body, and this feeling is something I hope to translate into image.”

“I tend to work on an image in an indirect fashion.”

“Once the composition is established, I paint the space around an object in an attempt to define the subject, rather than paint the object itself,” he says as we chat via Zoom.

He’s just returned from an expansive visit to Jovel, Mexico, the indigenous Tzotzil name for San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, having just completed a new series of paintings which will debut at the Clark Gallery in Lincoln, MA in July. “I think what they’re picking up on is this need I have to look at a scene from all angles. In everything I draw and paint and make, including music, the spirit is always bigger than the body. I do have this feeling of floating, of somehow being bigger than your body, and floating down the street.” Whether under the influence of San Cristóbal’s perpetually smoky air (the locals burn wood to heat their homes), the exquisite saffron tamales dusted with just an orange whiff of pollen-bitterness, or the magical electricity rising silently from the heaps and hoards of precious amber that beckon from gift shops, the new works deliver an emotional charge which feels entirely direct. Many of these new figures seem frozen in a pose of memory, like a fossil trapped in a stone that Saaf finds during his daily walks back home in Vermont, and later carves, or an ancient creature snared in the ancient golden resin of a drowned conifer forest. As we kept in touch during the completion of some of the new paintings, Saaf commented that he was adding “more spirits” to the compositions, sometimes in the form of haloed birds’ heads.

Another label he’d like to shed, perhaps, is the “craft” label which often finds its way to him since he often collages his paintings with scraps of patterned fabric snipped from thrift-store finds, bits of aged wallpaper, clippings from magazine ads and mail order catalogs, fragments of vintage sheet music, and snippets from old books, all sealed into place within the painting with an acrylic medium. Somewhat apologetically, he says “I try to be respectful of these old books, but I simply can’t use a photocopy. It has to be the real thing to have the aura.” Saaf will sometimes attach a piece of rag paper to board with gesso, then begin to build dense layers of paint and other textures as the painting informs him of itself and its intentions. He describes the true essence of a finished painting as “a conversation between the layers. Painting is a good way of capturing many different events and emotions occurring over a long period of time and condensing it into a single moment. If I am not happy with the way a face is painted, I draw it again on top of the original, and the face that I like lies somewhere in the space between the two. I like to leave remnants of all stages of the painting process.”

The layering process is essential to his understanding. Saaf says that he begins with a grounding base of acrylic in “organic, simple colors,” meaning ochre and earth-tones. “I may do a preliminary sketch, but I usually don’t spend a whole lot of time there,” says the artist. A second layer “cracks it open” with the addition of white pigment, followed by glazes of transparent colors and the sometimes by the application of cloth and paper elements. He says, “It’s an improvised, uplifted story. I’m never satisfied if I just draw a line. First, I lay the element in, the shape or the color. That’s the basic architecture of a story, and then I go in again and again and begin fracturing the painting until it’s like a stained glass window Some of the figures will have several heads; one that seems more solid and others that look more transparent and ghostly, hinting perhaps at the passage of time or suggesting that reality is more pliable than we usually think. They might be a representation of the soul or perhaps just a symbol for the many levels of personal consciousness.”

As a jazz aficionado, Saaf likens his process to listening to Coltrane. “If you listen to Coltrane’s take on ‘My Favorite Things,’ it’s this very simple melody. Coltrane will state the melody, then analyze it, and destroy it until it’s in tatters, then come back around.” He likens this process to kintsugi, the Japanese technique of restoring a broken pot or plate with a sealing scar of gold.

His recent trip to Mexico energized and affirmed his love of the unconventional, especially when dealing in the chromatic. “Mexico is so visually inspiring. I’ve thought about it constantly, ever since I first went there 30 years ago after I graduated from art school in the 90s, when San Cristóbal was this sleepy, dusty little town. Now, walking through those streets, you feel this constant waking-up of your brain. First, because of the presence of indigenous people, and the dominating presence of heavy Catholic imagery everywhere, every single object you see takes on huge meaning, and usually doubled or tripled meaning, like the syncretism the portrayal of a Christian saint that overlaps with an earlier native story. The color combinations are so shocking to me, coming from New England. They paint their houses in colors gone to such extremes,” he says admiringly, noting that the rosa Mexicana bright pink, paired with tangerine, turquoise, coral, marigold yellow, cobalt blue, neon lilac, would certainly raise the hackles of any tidy, neutral, modest, soberly self-respecting Yankee HOA in Vermont, Connecticut, and New Hampshire.

By contrast, he’s definitely not a fan of AI. He says, “Art is a communion with the soul of another human being. This is why I’ve always loved drawing and painting with kids, especially when I was teaching elementary school.” Saaf recounts spending childhood hours with his older brothers and sister, drawing comic books in the family basement, and says “You can make powerful art at any level, even when academic technique is not present. What I look for in painting is connection with another human soul. With AI, if you look at a picture long enough, you will only ever find numbers and code. When you look at a real, human-made painting, it enables you to virtually travel through time and come face to face with the soul of another Artist.”

Does this suggest that we’d all be better off if we stopped digging into our past? Saaf says no. He rallies by mentioning his fondness for vintage patchwork quilts, an affection which again mistakenly aligns him with the kitschier aspects of Americana. “As life goes on, I see mine like a beautiful quilt accepting both tragedy and beauty,” he says. “When you view your whole life as a quilt, the dualities or contradictions take on a different perspective. In an attempt to transplant this concept into a 21st century ‘folk’ painting, I’m moving away from the singular personal story line to one that focuses more on the community, and the great ocean of souls from which we all emerge. In one sense there is a story being told on the canvas but if you look closer, it’s made of colorful pieces of fabric with histories of their own; fabrics which are in turn made of individual, colored threads. It’s a harmonious collection of shapes and blocks of color that only tell a linear story in your imagination. Past, present and future merge and become more of a continuum, and so that makes it all a bit easier to take.”

This dualism also makes itself known in Saaf’s music which rocks a folksy, rootsy vibe on acoustic guitar and harmonica that the artist says is inspired by Robin Williamson of The Incredible String Band. Bob Marley was another major musical influence in Saaf’s youth, and he found joy of expression in the punk scene of 80s Boston. He says, “Now, I don’t know where to play. My parents were from Sweden. My dad played the harmonica, and when I am writing songs, I hear my mom’s voice, from Sunday mornings in church. My mom would sing harmony over the melody, and I do something similar now. Even when I’m singing harmony, I’m hearing the melody.”

Saaf’s manner is optimistic, warmed by the lingering sweetness of the Mexican sun and what he describes as his new chapter of life, with the promise of health, a new marriage, the couple’s move to Down East Maine, with plans to visit Merida, Mexico in a few months, and on a more regular basis. He’s no longer enamored of New England winters, which he describes as “brutal.” Discussing how cataracts impacted the life of Monet, he says “I have a sleepy eye. It’s not apparent to other people. But when I’m tired, that eye sees double and even triple, I see three of everything, so maybe what I’m painting is not as far-fetched as it might seem...maybe an Artist’s Vision is just their actual vision!””

All photos courtesy of the artist.