Toy Story Dreaming

by Victoria Thomas

We’ve all struggled, some time or another, to come up with a great idea.

Whether we’re trying to summon inspiration for an original kitchen redesign, or a creative gift for a finicky recipient, or a great line of dialogue for a tortured screenplay in progress, inspiration can elude us. In those moments, often in the dead-white hours just before dawn, we wonder where our Muse has gone, and why she has so cruelly deserted us.

Artists Mariko Kusumoto @marikokusumoto and Nick Cave @nickcaveart could not be more different, yet a quick plunge into their respective bodies of work can’t help but serve as an instant creativity-tonic. Kusumoto fabricates, Cave assembles. Both artists -- she’s in Boston, he’s in Chicago -- invite us to lose our minds, at least for a while, at least in the conventional sense. Kusumoto’s watery, gelatinous fiber creations may bring mermaid dreams, while her meticulous metal contraptions seem like the vintage wares of a truly strange toy-shop. And Cave’s world is even stranger, and deeper. Through this artist’s creations, starting with his famous “sound-suits,” we learn that the Collective Unconscious of Carl Jung’s writings is bouncy and Muppet-like, arrayed in dancing, jumping, shaggy, neon fake fur.

Thinkers and makers of all kinds often reference a child-like state and a sleep-like state -- some call it the Delta wave state -- as being the natural habitat of creativity. This submerged landscape of the imagination cannot be mapped, though Maurice Sendak portrayed it in his “Where the Wild Things Are,” and Guillermo del Toro described it cinematically in his film “Pan’s Labyrinth.” By definition, it’s a place unbothered by rational logic. Some would say the local language is magic. None of the words seem to make sense, but all are familiar, and somehow understood.

Any discussion of wild things, especially when discussing an artist whose surname is Cave, has to take us to rural southwestern France, near Montignac. The year is 1940, September 12. Four teenage boys follow their dog down a narrow stone path. Ducking under a low rock ledge, the boys literally stumble into a cavern of paintings from the Upper Paleolithic, dated at 15,000 to 17,000 years old.

Four teenage boys happened upon the Lascaux cave paintings by accident in 1940. These astonishing prehistoric galleries and their discovery serve as a metaphor for unlocking the Collective Unconscious.

As with the creatures of Sendak and del Toro (with a nod to the “Star Wars” cantina scene), the great stags and bulls and horses of Lascaux thunder unseen under our feet, just out of reach of our conscious perception, as they have for nearly 200 centuries. Likewise, the constellations -- Orion the Hunter and his dog Sirius, bears, scorpion, swan -- wheel and dance overhead in an ancient, revolving cocktail-party conversation just out of human earshot. Long before Jung, aboriginal cultures of every continent acknowledged the presence of primordial intelligence present in the stars and stones as the source of all human energy and knowledge. Today, modernists including Cave and Kusumoto guide us back into that hidden grotto of intuition, impulse, and non-empirical knowledge where creativity flowers freely with improbable blooms.

Nick Cave, an Alvin Ailey-trained dancer, began making his sound-suits in response to the savage beating of Rodney King by the LAPD in 1991. Encountering his works without knowing this backstory, the sound-suits hardly seem the stuff of activism. Cave recounts walking in a park soon after learning of the attack on King and his passengers, and noticing a stick on the ground. The stick, he said, seemed to epitomize something unwanted and worthless. He picked it up, and began collecting twigs and sticks around his neighborhood, eventually assembling them into the first “sound-suit.” The piece was intended to be worn, with its layers of small sticks producing audible rattles and clicks, coded messages of the unheard, unseen, silenced Black man inside the shamanic garment.

Cave’s imagination took off from there, and he quickly integrated a giddy flea market esthetic to his later suits, pairing yards of faux fur in day-glo colors and sequined fabrics recalling Haitian drapo (voodoo flags) with parts of broken dolls, repurposed doilies and fabric scraps, pieces of plastic, trinkets, ornaments and junk-drawer ephemera. The effect, which Cave states was unplanned, calls to mind Voudoun offerings and many talismanic African forms.

Kusumoto’s creations are tranquil by comparison, drifting into the subconscious like a siren-song, versus Cave’s more kinetic, percussive drumbeat. Many of her forms resemble transparent sea-life, making her jewelry a dreamy favorite in museum gift-shops.

Using a proprietary heat-setting technique, she crimps, pinches, pleats and molds sheer polyester, nylon and cotton fabrics into pristine, pastel reefs and ruffles. Her technically superb execution of ridged textures, mimicking the micro-grooved surfaces of a miniscule insect ovum, takes this work into the realm of the sublime.

The Japan-born artist describes her work as innocent, child-like and playful, citing the tiny plastic charms sold in vending-machine capsules as the direct inspiration for some of her most popular bracelets.

There’s also the sense of something less pretty in this work, which ultimately is what gives Kusumoto’s creations their persisting allure.

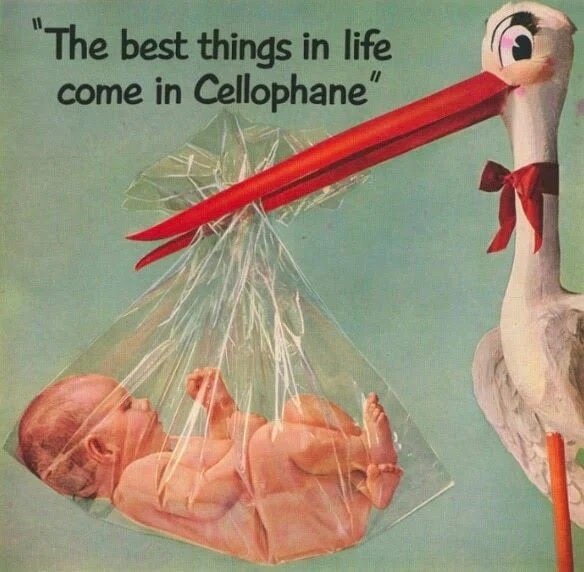

Anything enclosed in a gelatinous sack suggests egg-laying, incubation, developing embyros, and metamorphosis, creating a more mysterious, generative, slightly menacing energy in these superficially candy-like pieces. Any reader of classic fairytales will be reminded of the sweets-encrusted “sugar shack” witch’s hut in the Grimm Brothers classic, Hansel and Gretel. And her mechanical metal insects seem sure to provoke a Burroughs-Kafka-esque shudder in even the sunniest of dispositions.

As with all works of art, it’s in the eye of the beholder.

Kusumoto’s translucent confections seem sweet, but also carry an ominous edge suggesting primal, jelly-bound gestation -- even an eerie array of plastic-bagged thrift-shop Barbies.

All Mariko Kusumoto photos supplied courtesy of the artist

Photos of “Minnesota Savers Barbies” provided by photographer Victoria Thomas.

All Nick Cave photos and all other photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.