why opera matters

by Victoria Thomas

Let’s begin with Long Beach Opera, founded in 1979 in Long Beach, California, making it the oldest operatic producing company in the metropolitan Los Angeles and Orange County region. The company expresses its mission this way: “To engage people through provocative, meaningful experiences that challenge, connect, and inspire.”

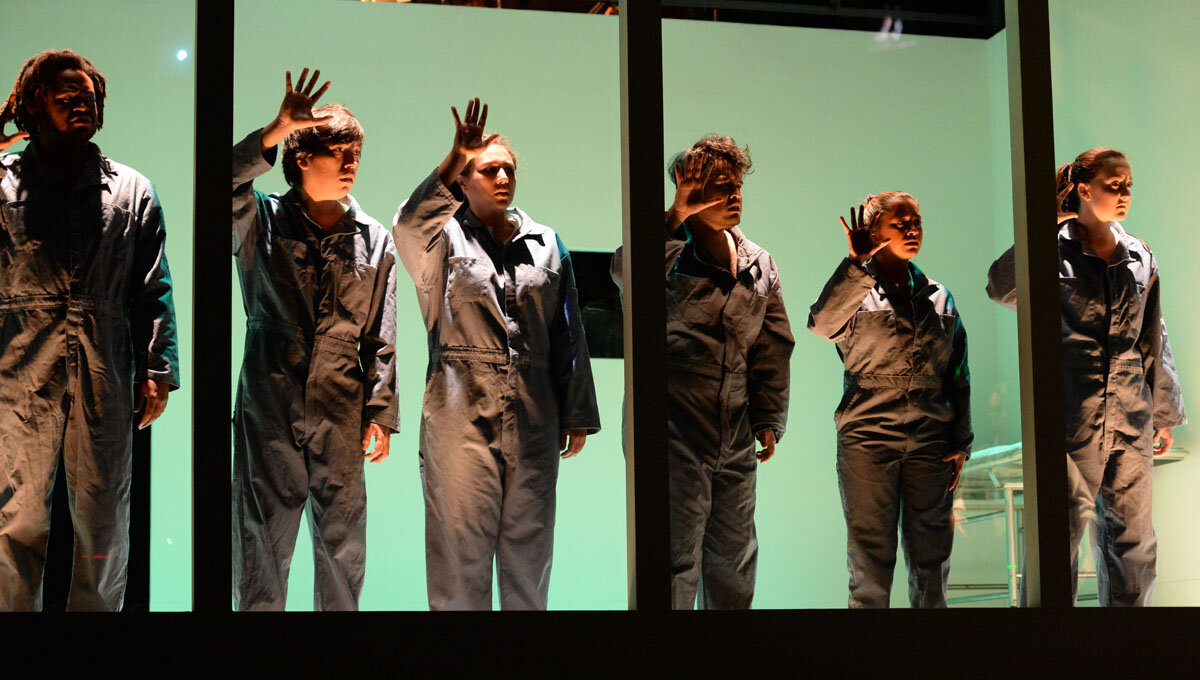

On August 14 and 15, 2021 at The Ford Theatre, Long Beach Opera presents a daring pair of solo operas that defy any notion that opera can’t address salient political concerns, specifically the concerns of women. Two operas, written a century apart, are on the bill: Pierrot Lunaire (1912, Arnold Schoenberg) and Voices from the Killing Jar (2012, Kate Soper).

The surreal, absurdist Schoenberg score is recited in sprechstimme style, and the Soper is atonal, unhinged, mysterious. Neither falls into the category of easy listening, even by opera’s rarified standards. And for those uncertain about making a foray into the opera experience, the radical bill might serve as the equivalent of a welcome mat which reads “GO HOME” (or, “Surrender, Dorothy”).

Image courtesy of Long Beach Opera

Jennifer Rivera, General Director and CEO of Long Beach Opera, disagrees. “The best entry-point for someone new to opera may not be ‘La Boheme’,” she said via telephone with Soolip. “Our work is to create a space for what is contemporary and relevant, and we believe that doing this will draw new, diverse audiences to this form which is at once so beloved, and yet so maligned, especially in America.”

Choreography and full, “big theatre” production, she points out, will make the thornier aspects of the programming more digestible. “Typically, these two works have been performed in a very sparing way, but we’re using staging and visual storytelling to bring the challenge of the music to life.”

Perhaps the most essential question about opera is not whether or not it is relevant, but rather how it is intended to be enjoyed. Opera arrived in most American homes at the 20th century’s turn, via the RCA Victor Company, which pressed the first recordings of Enrico Caruso’s voice to demonstrate the fidelity of its early audio technology.

Parody proved irresistible. Generations of school-children (myself included) heard classical music including opera every Saturday morning in the form of Bugs Bunny cartoons from Warner Brothers, notably “Long-Haired Hare” (1949) and “What’s Opera, Doc?” (1957). Stereotypes took indelible form: the sweating, bellowing tenor, and the enormous, immobile soprano, clad in a helmet crowned with horns. Comic Adam Sandler’s excruciating “Opera Man” character in SNL perfectly captured the essence of why many people think they hate the form.

Yet the music itself has continued to work its alchemy, even through the most cynical of times. There’s no denying the goosebump-raising thrill as Robert Duvall in the role of Lieutenant Bill Killgore air-checks Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” in the film “Apocalypse Now” (1979): “Big Duke 6 to Eagle Thrust, put on Psy-War-Op, make it loud, this is Romeo Foxtrot, shall we dance.” And new operas began to tackle vast, dark, modern subject matter—2005’s “Dr. Atomic”, for example.

Was opera ever fun? History says yes, not only in the form of opera buffa, but in terms of general come-as-you-are attitude. In the early 19th century, many Italian operas were punctuated by an Aria di sorbetto, a short solo performed by the cast’s second banana. This break late in the second act allowed the audience to chat, gossip, preen, and, yes, lap up the refreshing sorbetti e gelatti sold by vendors moving through the crowd, before settling in for the finale.

The American experience was different from the beginning, where opera has always been clad in the suffocating finery of bourgeois wealth. Remembering that the great Caruso was a child of the Neopolitan ghetto (and Pavarotti the son of a baker and a factory worker) may have seemed like little consolation.

Modern advances in acoustical amplification only widened the gap between the audience and the generally grandiose storylines. Opera houses issued stern warnings about the distraction caused by unwrapping cough drops and hard candy during the performance. Studies were conducted on the physics of the crinkly plastic wrappers, confirming the bad news that noise generated by unwrapping—actually a small series of clicks and pops—was unavoidable, regardless of care or technique.

Beginning with the 2004-2005 season, Carnegie Hall installed boxes filled with Swiss-made Ricola lozenges outside the Isaac Stern Auditorium, offered to patrons at no charge as a solution to the problem. The lozenges themselves aren’t the point: the waxed paper wrappers, it turns out, are less noisy than the crackling plastic wrappers of competing brands. A 2018 press release indicates that Carnegie distributed 800,000 cough drops to patrons that season alone.

Image courtesy of Pacific Opera Project

Matt Cook, Executive and Development Director for Pacific Opera Project, (POP), recently spoke with Soolip by phone, and he’s hopeful about the future of opera. POP, part of Opera America and founded in 2011, will present “Cinderella” (“La Cenerentola”) on August 27, 2021 at The Ford Theatre as part of this year’s Fairytale Season. Cook explains that the season’s Fairytale theme emerged from the darkness of COVID. “We hear that our patrons are ready to get together again and need to have a ‘fun evening out’ more than they want a deeper, darker emotional experience. That’s our audience, at least.”

The company’s mission: “To provide quality opera that is innovative, affordable and entertaining in order to build a broader audience.”

POP’s Vision Statement goes even further: “In the future, opera will become a greater part of popular culture, as we develop a larger local community of opera-lovers and launch the careers of opera-makers.”

“When most people think of opera,” Cook says, “they think of a mostly white, European art form with elaborate sets and singers, belting high notes in other languages. Our Founding Artistic Director, Josh Shaw, often rewrites a classic libretto using a modern vernacular with subtitles in English. By performing classic operas from the historic canon (like Mozart’s ‘Magic Flute’), we welcome traditional opera lovers. By staging the ‘Magic Flute’ as if they were characters from a 1990s video game, we welcome a younger and brand-new audience to the art form. We like to think that if we get a new audience in the door, we can keep them. We also offer a low entry ticket-price to almost every show, normally the cost of a movie-ticket.”

Images courtesy of Pacific Opera Project

At POP, true to its name, pop culture informs the classics. Josh Shaw’s 2019 re-take of Madama Butterfly rocked the house with all Japanese roles being sung in Japanese by Japanese-American artists, and all American roles sung in English. The company’s production of Mozart’s “Abduction from the Seraglio” was staged as an episode of Star Trek, and Puccini’s weepiest favorite (“La Boheme”) returns every holiday season where crowds delight to the relocation of the opera to contemporary Los Angeles, where the characters assume the guise of under-employed, tragically-hip locals. In November, 2020, the company presented “COVID Fan Tutte” at a local drive-in theatre.

An issue under fierce scrutiny at POP and elsewhere is the blackface, yellowface and brownface historically tolerated when white artists are placed into non-white roles. Racism as well as sexism persists in the traditional stories. Cook explains, “It’s an area where we are currently doing a lot of listening. Our Artistic Director mentions always wanting to cast the best person for the role, unrelated to race. Having said that, sometimes race is an important part of the role. Tricky, no doubt.”

He adds, “To this point, POP hasn’t retold a production to make it more politically correct. Having said that, I think that certain re-stagings will have to happen to keep some of the classics in the canon.”

POP is now launching a new youth Education Program led by Community Engagement Officer, Telia Thiesen. Partnering with schools and local afterschool programs, the collaborative spirit sets the stage for POP’s planned future programming.

Working against the hoped-for expansion of opera is the fact that people sing in public less today than in generations past. Yes, Glee Clubs, choirs and choruses still exist, but the decline of music education in public schools, among other factors, means less unamplified singing in America.

Opera experts detect this decline in the dwindling number of the robust voices called “spinto”, which especially affects the singing of Verdi’s heaviest masterpieces (thankfully note that one of these, “Il Trovatore”, will be offered in a new production by LA Opera, September 18 through October 10, 2021).

“Spinto” translates from the Italian as “pushed”, and works including “Il Trovatore” require dense, powerful voices with edge, bite, dynamic and melodic flexibility, and warm, dark timbre, large and substantial enough to cut through orchestral textures with what is called “squillo”, or tonal slice. Case in point, Verdi’s “gypsy” (Romany) character, Azucena, who epitomizes the “pants” roles typically sung by mezzo-sopranos: “witches, bitches, and britches.” Aida and Otello are other Verdi standards that are currently out of favor, or at least rotation, due to the scarcity of spinto voices with sufficient “pulp” in the form of vibrato, and chest and laryngeal manipulation.

Another aspect of what’s happening in opera today is that the form has never been more visual. There’s no denying that powerful stage directors now may cast heavily on the basis of looks, not sound. Modern sopranos in particular are slim and chic, putting to rest the beefy stereotypes of librettos past.

The anatomical mass of history’s big voices established them as a force of nature, and the brute physicality of their technical work is not to be denied—especially in the recent past where they sang onstage without a microphone. Opera singers are the Olympians of singing, true vocal athletes who create an emotional landscape told with sound.

Remember that until recently, the vast majority of operatic singing was not experienced live, in a theatre: it was heard on a thick, slowly rotating Victrola record with a rasping needle, or over the radio, and then via LPs. With the advent of film, and now digital video, we see the monumental visceral effort required to hit and hold B4, a semitone short of C5, the tenor high C, as the tenor must in “Nessun Dorma”, the virtuoso tenor’s aria from Puccini’s “Turandot.”

At his bulkiest, Luciano Pavarotti tipped the scales at an indulgent 350 lbs. He seemed all pure, eye-rolling appetite, truly larger than life, in line with our preconceptions of the tenor. His mass made him the right man for the job, and lent a sacrificial and vulnerable aspect to his offering of his sublime gift: his voice.

For all of its polish, it is an act of daring. Those who dismiss opera as elitist have missed the point: at its most essential level, there is a carnal and vulgar aspect to opera, akin to the Roman delights of the circus, the gladiatorial ring, and the bullfight. It has to do with flesh being torn from bone, by force – including the force of love.

Pavarotti and all of the tenors who came before and now follow was a man on the wire, held only by the immediacy of human breath. His Herculean physique was merely an attempt to anchor himself against the fear of falling.

Image courtesy of Long Beach Opera

In the rise and hold of that tremendous instrument, the human voice, we feel risk, pain, and danger. This, moreso than the simple storylines or lush costuming, is why we continue to listen. At its best, opera makes us pinch ourselves to make sure we’re not dreaming.

Opera walks the line, to echo The Man In Black, who probably had no use for the stuff. Just as the great operatic vocalists transform emotion into sonic and visual art, especially with the intensity of live performance, opera companies including Long Beach Opera navigate the wire like a gymnast in a Fellini movie.

Jennifer Rivera says, “We place an importance on pushing the envelope all the time. The fact that we’re about to premiere two really atypical works that may make people uncomfortable is not an accident. This is terra incognita. Nobody really knows the libretto. So it’s fair game for young audiences, audiences of color, all of the people who want the experience that opera promises, but may have been turned off in the past by the cough-drop rules and other barriers to really showing up as you are, right here, right now, and engaging in the experience.”